Seeing COP30 through Ditwah’s devastation

Sri Lanka’s deadliest storm in decades puts the climate crisis in focus

By Sanjali De Silva

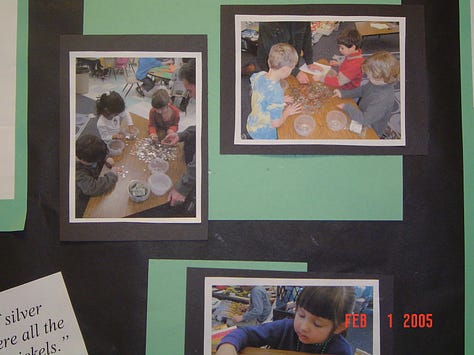

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami is one of my earliest memories. Thousands of miles away from my family near the impact zone, I tried to comprehend devastation far beyond what my five-year-old mind could hold. I emptied my piggy bank and asked my classmates to join me. It was the only way I knew how to help.

Twenty years later, I was leaving Belém after COP30 when Cyclone Ditwah tore across Sri Lanka. When I switched my phone on, it was filled with images of flooding and destruction we’re all too familiar with—except now it was scenes from the coastlines and towns I grew up in, through the eyes of my family in group chats. This time, there was no confusion about what I was seeing. This was a climate disaster.

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has called Ditwah “the largest and most challenging natural disaster in our history.” As of the latest reports, at least 350 Sri Lankans have been confirmed dead, with hundreds still missing. The 2004 tsunami exposed how vulnerable coastal communities were and how unprepared systems were for catastrophe. Sri Lanka rebuilt back then through extraordinary resilience, strengthening early-warning systems, overhauling disaster management institutions, and reshaping how it thinks about national risk.

But the world around us has changed. Today’s threats are different and more relentless. The tsunami was a geological shock. Ditwah, on the other hand, is part of a growing pattern of climate-charged storms that are intensifying as the world fails to cut emissions. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, fueling heavier rainfall, while warmer oceans provide the energy that allows cyclones to strengthen rapidly.

Scientists—and even oil and gas companies themselves—have known this since the 1970s, yet the world has still failed to act at the pace the science demands. While Sri Lanka contributes only around 0.1% of global emissions and the climate crisis, wealthy countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, and Norway have increased fossil fuel production by nearly 40% in the past decadeé

Ditwah struck Sri Lanka on the heels of COP30, where, despite half a century of understanding what causes this crisis, countries failed to advance promises to phase out fossil fuels. For frontline nations like Sri Lanka, this delay is deadly. COP30 also put in focus how Sri Lanka and other vulnerable countries face an impossible question: how to move as urgently as the global transition requires when those responsible for the crisis continue to avoid paying what they owe—both for cutting emissions and for helping countries adapt to escalating impacts.

Even as fossil fuel ambition fell short, COP30 did deliver progress. Countries agreed to triple global adaptation finance—a long-overdue boost in funding so frontline nations can reinforce coastlines, upgrade infrastructure, protect crops, and prepare for storms and floods like Ditwah. But it remains far below what is needed for nations repeatedly battered by climate-driven storms and burdened by debt. The Just Transition Mechanism established at COP30 is also a step in the right direction, marking the furthest the COP process has ever gone in acknowledging the realities workers and communities face in this transition.

Sri Lanka cannot rebuild its way out of this era. It needs global emissions cuts that reduce the fuel behind these storms. Sri Lanka needs predictable, accessible climate finance that reaches countries at the pace disasters are hitting us. And it needs a real, functioning loss-and-damage system that helps families recover from what cannot be prevented.

COP30 ended with the same truth Sri Lankans saw in Ditwah: we are doing everything we can, but without justice from the world’s biggest polluters, it will never be enough. The transition cannot be fair if the countries that caused the crisis refuse to cut emissions and refuse to pay for the damage they created. Sri Lanka rebuilt after 2004. It will rebuild after Ditwah. But rebuilding is not a climate strategy. The world must keep its promises—on fossil fuels, on finance, on loss and damage—before the next storm writes another chapter in this preventable history.

Sanjali De Silva is a communications strategist specialising in international climate diplomacy and global climate policy.